On Wednesday evening I attended a party at Vitra celebrating the publication of a long overdue monograph on architect Jean Tschumi, written by Jacques Gubler and

published by Skira.

Jean Tschumi: Architecture at Full Scale documents the brief career of the Swiss architect who eschewed his Beaux Arts training in favor of "the polemical field of modernity and its technological expression." In the US, the name Tschumi is more well known prefaced by

Bernard, rather than Jean, who died in 1962 at the age of 57, when his son was only 18 years old. His early death may have cut his architectural career short, but the quality of the architecture that he produced is evidenced in the pages of this monograph and in the

Archizoom exhibition last year, curated also by Gubler.

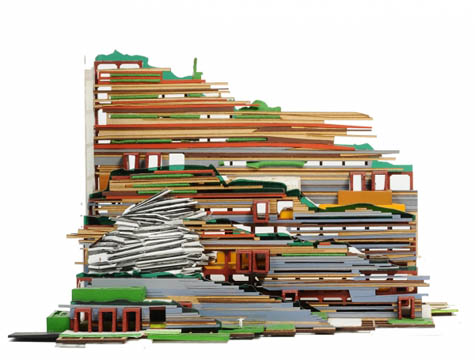

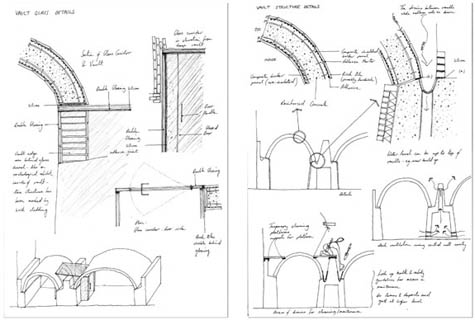

I'm especially taken by the image on the party invitation of the

Aula de Cèdres, a conference center and auditorium at HEP Lausanne:

On Wednesday Gubler spoke of Tschumi's architecture relative to color (embraced by the architect, but rarely captured in documentation of buildings) and scale, referring to the book's subtitle and the architect's consideration of design from furniture to the city. The book offers an in-depth exploration of Tschumi's career, which includes a number of office headquarters, for

Nestlé,

La Mutuelle Vaudoise, and the

World Health Organization. (

This blog post at New Switzerland gives a decent overview of the qualities of Jean's architecture.)

One is tempted to break down how the father's architecture influenced Bernard Tschumi's, though if an influence on the latter is evident, it is in the year's since his father's passing. Some brief words on Wednesday by the architect of the

new Acropolis Museum pointed to little discussion between the two regarding architecture. In fact

Bernard admits that he didn't decide to pursue architecture until a trip to Chicago, only a few weeks before his father died. But with time to study his father's buildings, and a role in

Architecture at Full Scale, it would be difficult not to find Jean's influence on his son.

[new Acropolis Museum | image

source]

Looking at the two buildings shown above, I would say the influence of Jean on Bernard happens primarily with thinking about site. The above clearly illustrates how the new Acropolis Museum's top relates to the distant Parthenon, while the lower floor contends with the ruins preserved below. In between, the museum is all about movement and the clarity of the exhibition, but it can be seen as the byproduct of contending with the site below and distant. The elder Tschumi's HEP building skillfully addresses the site's topography (as can be

seen here) and adjacent buildings, standing out formally but fitting into the multi-faceted landscape.

In the Wednesday-night party's introduction by

Nina Rappaport, Chair of

DOCOMOMO-New York/Tristate, the preservation of Jean Tschumi's architecture in Switzerland was commended, an unspoken difference between an appreciation of Modernism's gems and the demolition of the same

in part or in full an ocean away. The

US chapter of DOCOMOMO (international working party for DOcumentation and COnservation of building sites and neighborhoods of the MOdern MOvement) includes ten regional chapters (all tolled the international

DOCOMOMO is 53 chapters strong), but fights for preservation seem

to be lost more often than won.

While this fact points to a limited appreciation in this country for architecture produced in the middle of last century, I can't help but wonder if this situation is more about ideology than taste. Modernism was predicated on progress and responses to the changes sweeping across the developed world from industrialization and world wars, so the preservation of the movement's buildings seems anithetical to their origin. That people equate modern architecture with the tabula rasa clearing of neighborhoods, towards the erection of towers in the park in that time does not help matters.

A couple issues further complicate matters: how many modern buildings were not built with the longevity of buildings centuries before; the open plans and platonic forms of modernism did not turn out to be as flexible as envisioned. These point to the necessity of preservation less than 75 years after many buildings of the era were completed and the creativity needed by architects to propose and carry out the adaptive reuse of modernist structures. I think the latter is key in efforts to preserve modern architecture, especially when faced with opponents arguing that demolition and new construction is cheaper and therefore better. The fact that many modern buildings are ingrained and important elements in their neighborhoods (ironically, like the older buildings many modern structures replaced) is perhaps the strongest argument for DOCOMOMO's continued relevance today.

[Image: "Moravian Mount" from

[Image: "Moravian Mount" from

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: "House of Drink," "Greenhouse," and town plan from

[Images: "House of Drink," "Greenhouse," and town plan from

[Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Image: Michael Light, Bingham Pit photograph mounted and on display].

[Image: Michael Light, Bingham Pit photograph mounted and on display]. [Image: Two photos from

[Image: Two photos from  [Image: Michael Light, "Garfield Stack, Oquirrh Mountains and Ancient Beach of Great Salt Lake" (2006)].

[Image: Michael Light, "Garfield Stack, Oquirrh Mountains and Ancient Beach of Great Salt Lake" (2006)].

.jpg)